Presented at Devoxx France 2015 by Alexandre VICTOOR and Thierry ABALEA

Elucidation by Thomas SCHWENDER (Softeam StarTech Java)

- Bank is an other Big Data domain

- Code optimization: Cache and Hardware Memory Architecture

- Benchmark to be sure!

- Multithreading is not always the solution

- Other ways to go faster

- Logs

- Final advise

- Ressources

Bank is an other Big Data domain

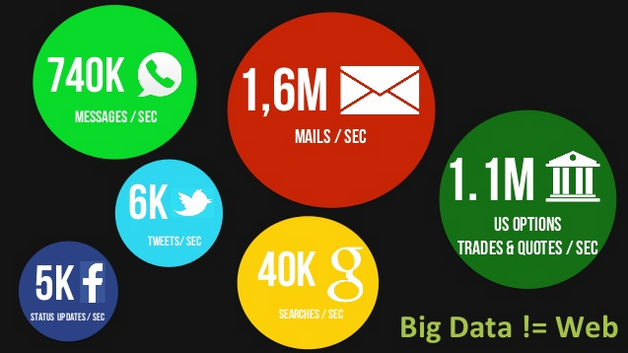

Alexandre and Thierry explain us that Big Data isn’t only for Google, Facebook and Twitter.

Bank is an other big consumer / producer of data.

The need for speed (for financial transactions) is so high, that even the optical fibre is not enough.

Because of the refractive index of the light in the heart of the fibre (1.5), it’s "only" the half of the speed of light in vacuum.

To address this problem, trading companies are now using microwave communication.

Take a look at this article of the Financial Times if you want to know more on this speed race.

Code optimization: Cache and Hardware Memory Architecture

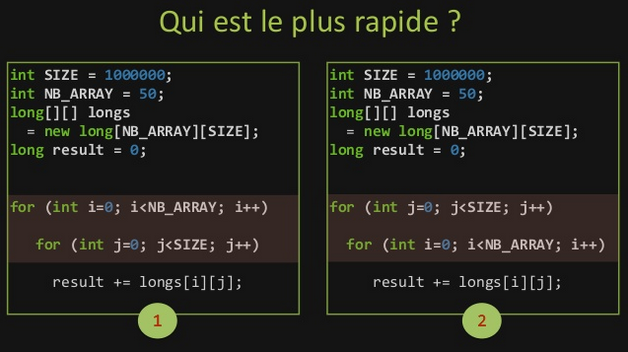

A first example puts forward the good comprehension of caches working in modern hardware memory architecture (meaning in multicore processor).

This example is a comparison of a 2D array traversal, which ends with the left program being much faster than the right one.

|

This is the consequence of one of the main principles behind cache: spatial locality (the other being temporal locality).

|

Here, the left program traverses the array a row at a time, thus reading the memory sequentially.

But, the right program does it column-wise, and so, after having read an entry, jumps to a completely different location (the start of the next row), and repeats this working all along the traversal.

So, when finally getting back to a previous row, it will probably not be in the cache anymore.

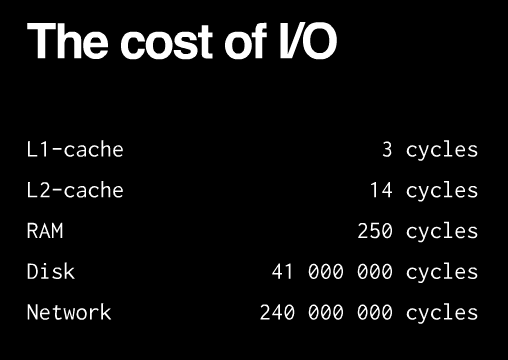

A quick reminder of the cost of I/O:

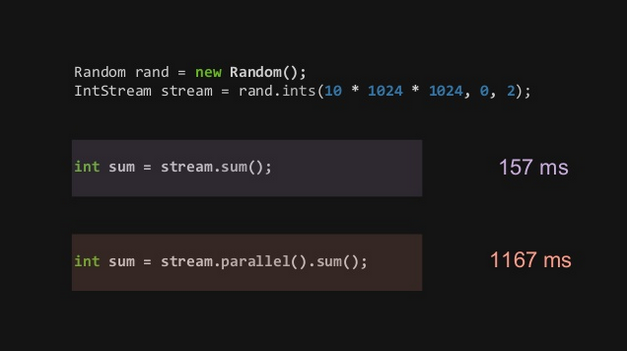

Benchmark to be sure!

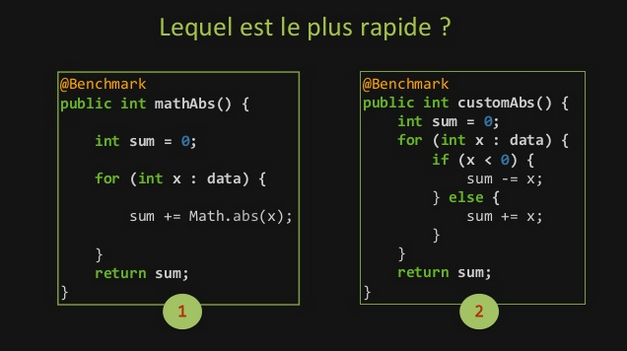

| Do not assume which is the fastest! Benchmark to be sure! |

OpenJDK JMH (for Java Microbenchmarking Harness) is the new "hot" tool to build, run, and analyse nano/micro/milli/macro benchmarks written in Java (or other languages targeting the JVM).

Its main advantage over other frameworks is to be developed by the same guys in Oracle who implement the JIT.

Multithreading is not always the solution

Do not forget that the setting up of multithreading always as a cost.

Depending on your process duration, this extra time can really be NON-neglibible.

| Again, do not assume it will be faster, benchmark it! |

Other ways to go faster

To avoid a brutal use of multithreading, Alexandre and Thierry propose some asynchronous architectures.

Even if that wasn’t the main purpose of this conference, they also said a few words on hexagonal architecture, which also was a "buzz" word during the whole show. Here is a quick explanation about it.

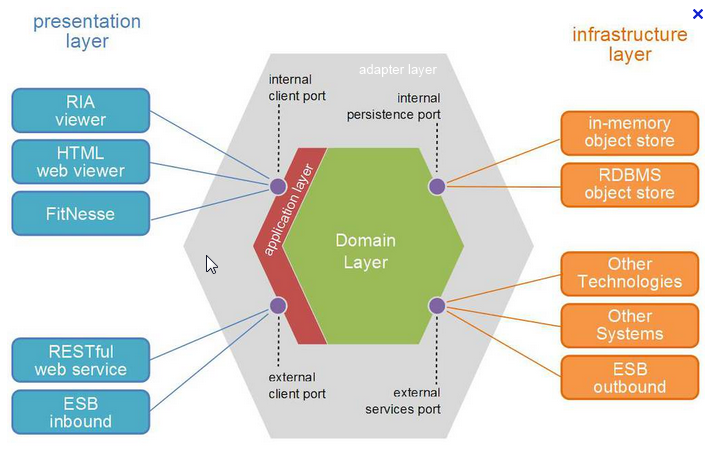

Hexagonal architecture

The main purpose of hexagonal architecture (or Ports and Adapters architecture) is an old one: to clearly separate business from technical implementation.

Its underlying principles are summarized in a hexagonal schema:

-

the domain layer is at the center of the hexagon, in green. It contains the business logic of the application.

-

the ports layer, around the domain model, receives all the requests that corresponds to a use case that orchestrates the work in the domain model.

-

the adapters / connectors, that allow communication with the outside, are in grey outer hexagon.

-

all that is at the left of the hexagon represents those that need it.

-

all that is at the right of the hexagon represents the components that the hexagon needs.

|

The purpose of this architecture is to defined business-centric modules whose business layer has no dependency with any technical part. |

Now, let’s come back to our asynchronous alternatives to brutal multithreading.

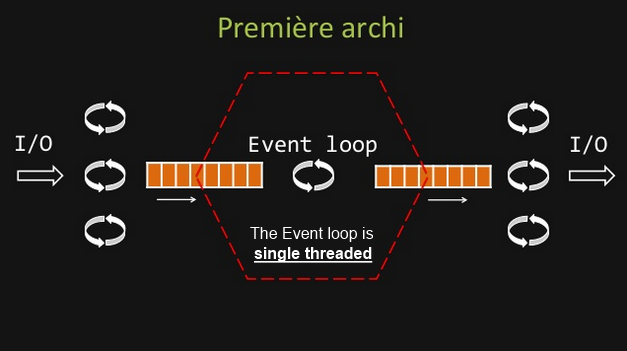

Event loop and queue MPSC (Multiple Producer Single Consumer)

|

A definition of the Event loop could be: |

The important thing to remember is that the Event loop itself is single threaded.

In the current architecture, it reads its inputs from from a Multiple Producer Single Consumer queue.

So we are not creating a new thread for each new input, but are relying on the dispatching of the single threaded Even loop, which is better.

Now, if we want to be even faster, we must consider that the MPSC queue being NOT lock free, it can be a bottleneck in case of huge volumetry.

Effectively, with locks, you must pay for:

-

system calls

-

context switch

So, let’s now present a lock free alternative.

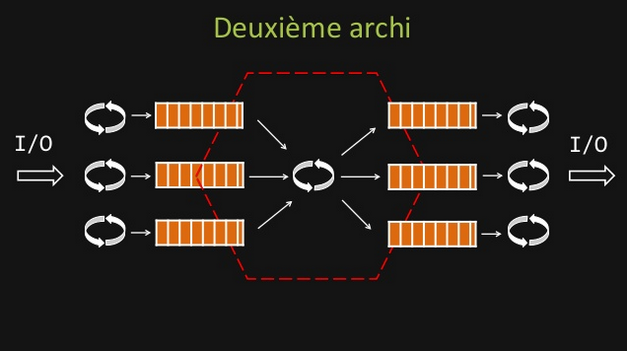

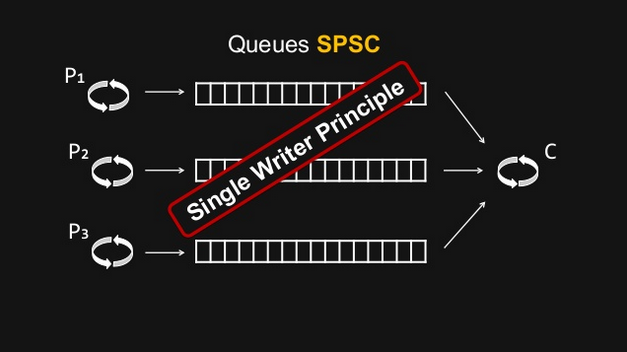

Event loop and queues SPSC (Single Producer Single Consumer)

In this case, we do not use anymore Multiple Producer Single Consumer queues, but Single Producer Single Consumer, lock free ones.

By doing so, we respect the Single Writer Principle, hence our threads do not contend for the right to write.

The Single Writer Principle is that for any item of data, or resource, that item of data should be owned by a single execution context for all mutations.

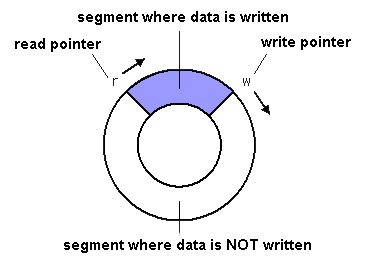

An example of lock-free SPSC queue: the Ring Buffer

The Ring Buffer, or Circular Buffer, was one of the buzz word of the performance oriented presentations of the conference.

It is a first in, first out (FIFO) data structure that uses a bounded (fixed-size) buffer, as if it were connected end-to-end.

You use to pass stuff from one context (one thread) to another.

One of its useful characteristic is that items in the buffer are never moved.

Instead, changeable pointers are used to identify the head and tail of the queue.

With one reader and one writer (SPSC), the Ring Buffer is a lock-free and wait-free FIFO buffer.

|

Beware when reader and writer indices remain too close. In this case, you’ll have each thread constantly invalidating a shared cache line. |

The volatile keyword: an efficient design for memory synchronization

volatile is Java keyword about which much was written, especially since its definition changed as of Java 5.

From this version, it has the following characteristics:

-

rule 1:

The value of avolatilevariable will never be cached thread-locally: all reads and writes will go straight to "main memory".

That implies that different threads can access the variable. -

rule 2:

The adding of Java 5: accessing a volatile variable creates a memory barrier.

It effectively synchronizes ALL cached copies of variables with main memory. ALL, not only the lonevolatilevariable.

Therefore, it becomes possible to write to one variable without synchronization, and then take advantage of subsequent synchronization on a different variable, to ensure that main memory is updated with both variables. -

rule 3:

A write to a volatile field happens-before every subsequent read of that field.Happens-before relationship:

If one action happens-before another, then the first is visible to and ordered before the second.This implies that the reading and writing instructions of volatile variables cannot be reordered by the JVM.

Other instructions before and after can be reordered, but the volatile read or write cannot be mixed with these instructions.

Let’s illustrate that with the 2 following examples:

-

First:

// Thread A: sharedObject.nonVolatileInteger = 123; sharedObject.volatileInteger = volatileInteger + 1;

// Thread B: int volatileInteger = sharedObject.volatileInteger; int nonVolatileInteger = sharedObject.nonVolatileInteger;

-

Since Thread A writes the non-volatile variable

sharedObject.nonVolatileIntegerbefore writing to the volatilesharedObject.volatileInteger, then BOTH variables (rule 2) are written to main memory (rule 1). -

Since Thread B starts by reading the volatile

sharedObject.volatileInteger, then BOTH thesharedObject.volatileIntegerandsharedObject.nonVolatileIntegerare read in from main memory.

That illustrates rule 3: volatile read or write can NOT be reordered with other instructions.

-

-

Second:

public class StoppableTask extends Thread { private volatile boolean pleaseStop;public void run() { while (!pleaseStop) { // do some stuff... } }public void tellMeToStop() { pleaseStop = true; } }Let’s say Thread A reads the

pleaseStopvariable, and Thread B writes it.

IfpleaseStopwere not declared volatile, then it would be legal for the Thread A (running the loop) to cache its value at the start of the loop and never read it again.

That would mean that, even if Thread B writed inpleaseStop, it would end in an infinite loop.

With volatile rule 1, both threads are guaranteed to share the samepleaseStopvalue (because read and written from main memmory).

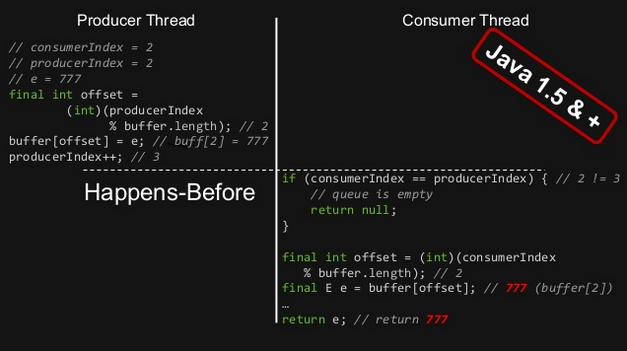

In the case of the former Ring Buffer, with the following variables declaration:

private final E[] buffer; private volatile long producerIndex = 0; private volatile long consumerIndex = 0;

We know that we would obtain this:

It is guaranteed that the write of producerIndex (producerIndex++;) happens-before its subsequent read (if (consumerIndex == producerIndex)) (rule 3), and that those read / write synchronize ALL cached copies of variables from main memory (the buffer variable here).

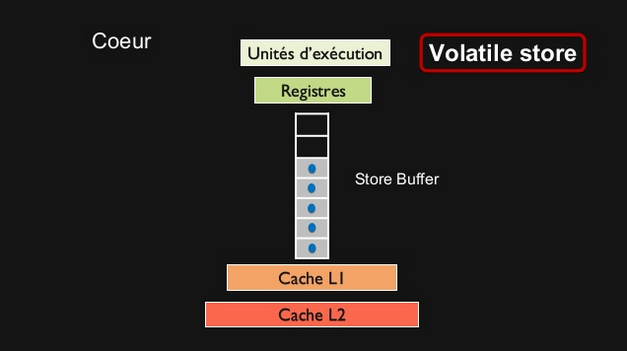

Volatile and performance

Reading and writing of volatile variables causes those last to be read or written to main memory, which is slower than accessing the CPU cache.

Moreover, writing a volative variable implies a flush of its underlying store buffer, which has a cost.

|

Volatile store buffer: |

|

As a consequence of this performance cost, only use volatile variables when you really need to enforce the visibility of variables. |

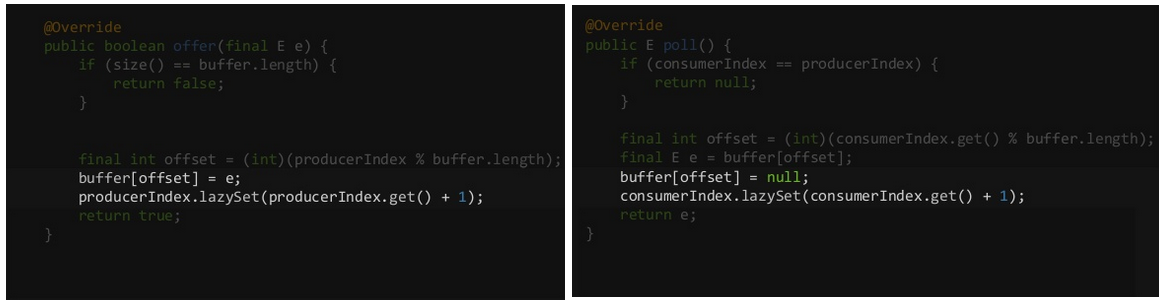

java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicXXX to overcome volatile performance

When only wanting to ensure memory ordering across Java threads (meaning you are not interested by ensuring data visibility to other threads, see volatile rule 1), instead of setting a volatile variable, you can use the lazySet method of Java atomics (see AtomicInteger, AtomicLong, AtomicReference, etc.).

By doing so, you do not pay for the volatile underlying store buffer flushing.

Using atomics instead of volatiles, we can still improve the precedent ring buffer implementation:

private final E[] buffer; private final AtomicLong producerIndex = new AtomicLong(); private final AtomicLong consumerIndex = new AtomicLong();

This results in a ~3 times faster implementation.

Instruction Pipelining

Alexandre and Thierry presented the instruction pipelining through the following quizz:

In this case, that’s the 1st program which ~5 times faster, precisely because of this technique.

|

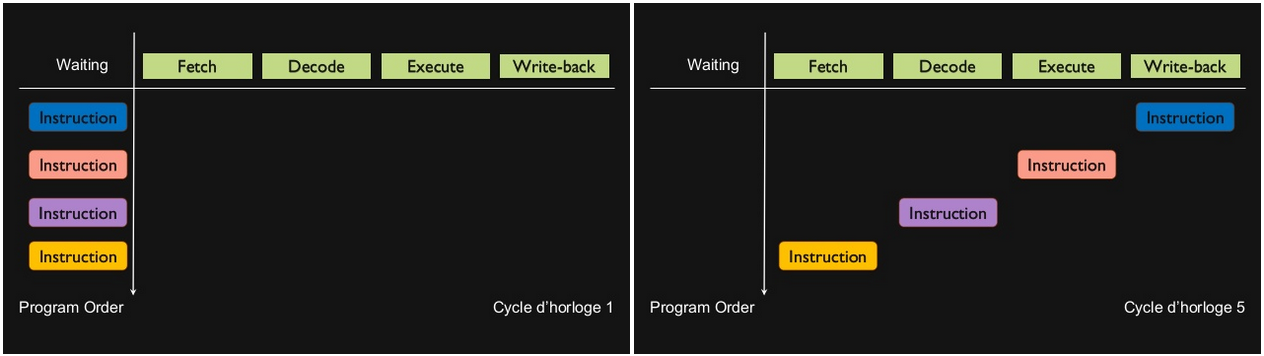

Instruction pipelining: |

The avantage of this technique is to increase the instruction throughput (the number of instructions that can be executed in a unit of time).

As each instruction is split up into a sequence of steps (Fetch / Decode / Execute / Write-back in the current example), those last can be executed in parallel.

|

Be aware that we are speaking of parallel processing inside one thread, which is NOT multithreading. |

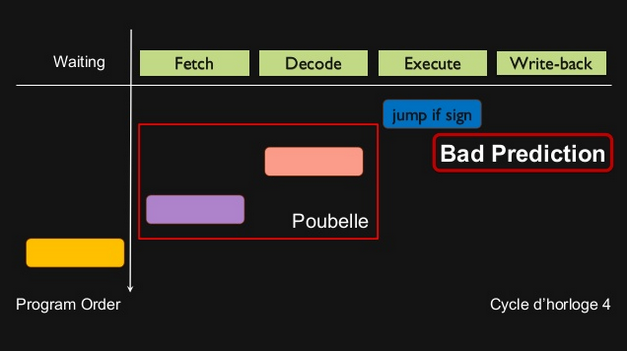

In the current example, the reason why program 1 is faster than program 2 comes from a matter of prediction.

Program 2 is based on a if / else statement.

If we want the processor to be able to execute instructions, without knowing in advance the result of this if / else statement, it will have to do a prediction.

This prediction is done by a branch predictor component of the processor, that acts based on the instructions history.

If only else were done in the past, it will try an other else next time.

Understandably, there will be some bad predictions, with the result of nullifying the next results.

On the contrary, program 1, using Java native Math.abs method, is based on a simple ternary operator.

This operator doesn’t imply prediction, and so, is not concerned by bad predictions (also called hazards), hence the better performance.

Logs

When facing high volumetry, logs can quickly become a high performance cost.

Classic log writing in a file is blocking, which is a problem.

To solve it, we can use a buffer, but if the process crashes, we lose its content, which is another problem.

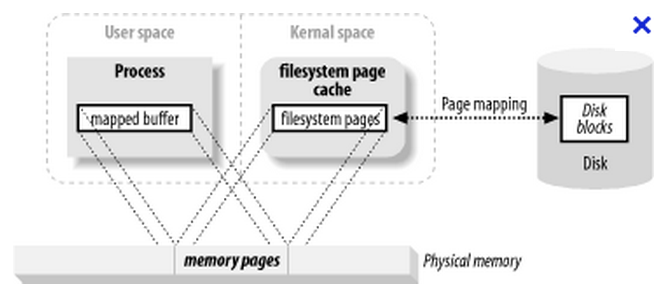

To solve both those last, Alexandre and Thierry put forward the Chronicle-Logger API from Peter Lawrey, which is based on a memory-mapped file.

|

A theorical definition of a memory-mapped file: |

Simplier, a memory-mapped file is a mechanism that synchronizes a memory area of your RAM with your hard drive.

Characteristics:

-

Memory-mapped files are stored off-heap.

-

It’s a very performant, fast, solution for big files, but is not recommended for smaller ones (probably slower than a classic access).

-

Once you wrote to the mapped memory area, then, later, asynchronously, the operating system will flush those writings to the disk.

So, from the moment the initial writing in the memory area is done (and it’s rather quick), even if the Java process then crashes, the OS will still be able to flush the data to the disk. That way, you are far less likely to lose the last log message.

|

Even if its underlying memory-mapped file implies an asynchronous data flush by the OS, the Chronicle-Logger is a synchronous logger (contrary to Log4J |

You can be even faster by logging binary data rather than text (it, of course, depends on what you have to log.)

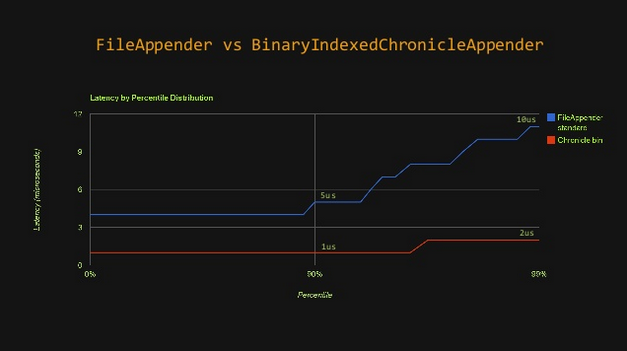

Here is a quick comparison (using HdrHistogram, see below) of a classic FileAppender against a binary appender, using a memory map file, from Chronicle-Logger:

Even in the worst cases

Final advise

|

Never assume about the latency of your solution, MEASURE IT! |

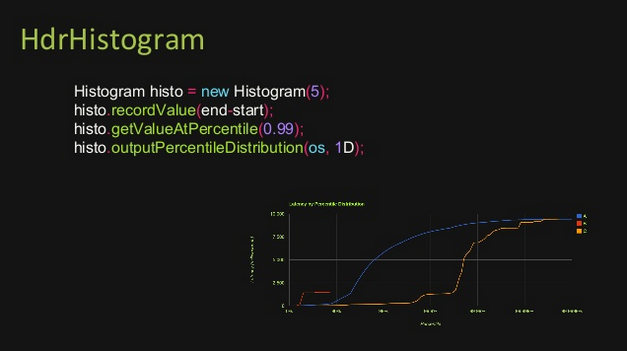

As already explained in presentation Understanding latency and application responsiveness from Gil Tene, do not trust averages, which can hide some behaviours, prefer the use of percentile.

For that you can use his open source tool: HdrHistogram

Ressources

Slides and video of the presentation:

The ressources I used to dig deeper

-

Java Memory Model & cache understanding ressources

-

Event loop, queues and circular buffer ressources

-

Volatile ressources

-

The volatile keyword in Java (and all linked pages, GREAT RESSOURCE) - Neil Coffey

-

Happens-before relationships with volatile fields - Stackoverflow

-

the Java Language Specification - §17.4.5 Happens-before Order

-

CPU cache flushing fallacy - Martin Thompson, especially check the Concurrent Programming section

-

-

Memory-mapped file ressources